During the dry season, the roads in Katakwi turn into a long ribbon of ochre, sinking into the occasional pothole and running through intermittent dust storms. So, it was no fun when the air conditioning in our Land Cruiser walked off the job in mid-afternoon yesterday. The car was packed with five of us, our luggage and several cases of Bibles we are bringing for the pastors in the region. We were headed to Usuk (pronounced OO-sook) and Ajoatorum, the village of Simon Peter Ojaman.

We first met Simon more than ten years ago. At that time, the whole area was essentially a refugee camp — hundreds of thousands of people fleeing the destructive wave of the Kony rebellion and the Lord’s Resistance Army. Today, the area has been resettled, many of the cattle have returned, and the villages are peaceful. Simon, once a young man in his twenties with an ambition to go to vocational school, is now a husband, father, district counselor and a prominent leader among his people. [For more on Simon’s story, click here].

We finally did make it, dusty and tired, and were greeted like royalty. We shared greetings, had something to eat, walked around Simon’s property, inspected my white cow, Lily, and her jet black calf, and turned in early.

Today is the day of the thanksgiving ceremony, a sort of East African potlatch. Even though this is a largely Roman Catholic district, Simon has told me repeatedly I am to preside and preach at a Eucharist, which will be the centerpiece of the day. I have done this once already, in a much smaller gathering, with Father Aloysius, a Roman Catholic priest, cheerfully serving as Deacon. Still, there will be 600 people here today, and it strikes me as odd that I would be allowed the same privilege in a crowd this size.

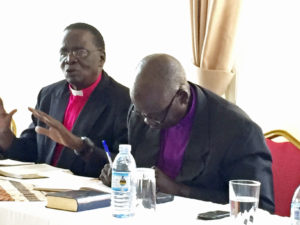

My reservations turn out to be warranted. Prior to the ceremony, I meet with two Roman Catholic clergy, Father Wasiwasi and Father Paul, priests new to the parish whom I have never met, and as I outline my understanding of my role in what I thought was to be an ecumenical service, I can see in their shocked looks that this is not at all what they have in mind. In spite of Simon’s assurances, it is clear they have been sent by their superiors to say Mass, to preach, and to make it back to Soroti in time for the six o’clock service there. It is also clear that not a word has been mentioned to them by anyone about me. I backpedal at high speed, and the moment is awkward but saved. Father Wasiwasi asks me if perhaps I could give “remarks” at the conclusion of the service. You bet, Father. Happy to.

I am not sure what Simon was thinking, anyway. Betsy and I are given special clothes, and are expected to walk in the procession with the immediate family, in the position of godparents. My outfit is bright purple (I kid you not) as is Simon’s. He can bring it off, being black, tall and slender, but I think I look like an enormous grape. Fr. Dan is amused and helps me feel better by taking several pictures and promising to post them on Facebook. By contrast, Betsy has a lovely dress that is the mirror image of the one worn by Stella Rose, Simon’s wife.

The little clearing where the festivities begin is surrounded on three sides by plastic chairs under large canvas tents that provide shade from the searing sun. The crowd is already singing songs of praise as we enter. Betsy, Dan and I take our seats with the family on one side of the tent in which the altar has been set up. In the middle of the clearing, near the loudspeakers, are the cases of Bibles, in Ateso and English, along with Bible covers, waiting to be given away.

The Mass is brief by Ugandan standards, about an hour and twenty minutes. Fr. Paul’s homily is very good and the two priests lead with good humor and reverence, helped by an enthusiastic choir. Beyond the fifty catechists in attendance, few people come forward actually to receive. Betsy, Dan and I go forward for a blessing, which Father Wasiwasi earnestly gives. Afterwards, there are (of course) speeches. Simon stands and thanks every one and spends considerable time on Betsy and myself, recounting the decade of our help and friendship to the people of Teso, and I see that the rather cool regard of the presiding clergy is warming up fast.

During the speeches it also becomes clear that this is a political event as well as a social one. Simon is already a masterful politician, and singles out a dozen or so prominent friends to give their own remarks. He calls up one by one the leaders of various constituencies, and personally thanks everyone who has had anything to do with pulling off this day. Finally, he asks the representatives of the churches present to stand, and they do so in turn: Roman Catholics, Church of Uganda, two varieties of Pentecostals, Baptists, and two or three non-denominational assemblies — a remarkably ecumenical assembly.

When Fr. Wasiwasi asks me to conclude with my remarks, and I have thanked everyone I can think of, I shift to a little homily on Jesus’ famous assertion, “Whoever does the will of God is my mother, my sister, my brother.” I note that he was not rejecting his own family, but expanding it, and that the presence and work of Pilgrim Africa, along with Betsy, Dan and myself, is proof that God has done the same thing here, bringing great good out of the suffering which for so long engulfed this region. I ask the people to be reconciled within to one another within their own churches, so that the churches may continue to be reconciled to each other and work together for the common good and for the sake of the Kingdom. It’s all well received, and after the applause, we distribute the Bibles — 272 of them to pastors lay readers and catechists, Protestant and Catholic, blessed by a Roman priest and handed off by an Episcopal bishop and his wife.

At the end of it all we change clothes and head to Mbale for a meeting and retreat of the Ugandan and U.S. Boards of Pilgrim Africa. As we roar down the dusty roads again, I remember the first time I saw this area — the ruined villages, burned fields, huddled refugees, and I wonder if in the midst of this apparent peace and recovery, the churches are finally ready to come together to do great things.

Pastor Nano and the good folks at Saint Stephen’s Wilkinsburg had a surprise for me. Nano called me up about a week before I left and asked if the kids at the school could use some pencils and crayons. Of course, I said, “Sure.” So she brought over about 500 of each! Since I travel light, it wasn’t hard to get them all in the luggage.

Pastor Nano and the good folks at Saint Stephen’s Wilkinsburg had a surprise for me. Nano called me up about a week before I left and asked if the kids at the school could use some pencils and crayons. Of course, I said, “Sure.” So she brought over about 500 of each! Since I travel light, it wasn’t hard to get them all in the luggage.